In this post Xinglin Sun and Caroline Claisse from the Royal College of Art discuss what was the first of a series of workshops which took place as part of the ‘AHRC Videogames Network: Developing videogames and play for hospitalised children’,a network developed by Elizabeth Wood and Dylan Yamada-Rice from the University of Sheffield School of Education. The discussions and activities undertaken in these workshops allowed network members to collaboratively participate in the research and design aims of the overall project. In this workshop the group created a playful space within which participants could develop their ideas collaboratively.

This post is composed of material originally posted by Sun and Claisse on the project blog (http://iedgameresearch.wordpress.com/) which also contains summaries of the other workshop days as well as posts concerning the design and development of games for hospitalised children. All writing and pictures are the work of Sun and Claisse.

Background

The videogames network is developing videogames and play for hospitalised children. Currently, UK hospital play tends to be based on ‘traditional’ toys and games, with limited innovation in digital play, such as children using tablets/smart phones brought in by family visitors to access videogames. The network is exploring the considerable scope for development in the videogames industry, using expertise from the arts and humanities to co-create digital play opportunities that respond to the specific needs of hospitalised children, to stimulate their play experiences, imaginations and creativity when confined to medical and recovery spaces, and to connect with siblings and friends. The network for this project brings together academic researchers from different disciplines; videogames developers and hospital play specialists in a series of workshops, using multimodal and arts-based approaches.

The aim of the network project was to have three workshop days to explore the perspectives of each of the key participant areas: (1) hospital play specialists, (2) academics from Education, English, medical humanities and (3) the digital games industry. As well as a final workshop to bring together the themes that emerged from the initial three workshops.

First Workshop

We had our first workshop day which focused on hospital and medical perspectives on Wednesday 26th of March 2014. It brought together play specialists with artists and academics and featured short talks and workshops to inspire participants on the project’s main focus:

- The potential of play for supporting children in hospital and recovery spaces.

- How to inform the games industry about creating content for the design of videogames which blends both traditional and digital forms of play.

To start with, Kevin Hartshorn from Sheffield Children’s Hospital talked about his practice as a Play Specialist and emphasised the potential of play in hospital contexts. According to Kevin, play can help patients to understand and cope with stressful situations and encourage them to express their feelings and aid a quicker recovery. He described different types of play such as those for development, rehabilitation, post-procedural, distraction and bereavement. Play specialists use a variety of activities that involve free play to encourage children to express themselves using activities such as hand printing and hand casting. Other activities included memory boxes, which are used to remember a child with a terminal illness and can involve family participation in the making process.

Key points that emerged from the presentation:

- To what extent are children allowed to customize their hospital spaces? Children are encouraged to personalise the walls with possessions that are sometimes used as talking points.

- Is there capacity to develop a personalised play program? Perhaps by considering the patients’ developmental stage and grouping them in different categories such as, physical, personal social and emotional, communication and language, cognition and intellect. After which it is possible to better consider which activities can meet their personal needs. In relation to this, records of preparation and distraction are kept to allow consistency with individual patients.

Challenges and complications from the presentation:

- Using stories to illustrate difficult subjects – be sensitive to people’s beliefs (e.g. religion).

- Physical and communication restrictions that emerge from being in hospital spaces.

- Challenge in capturing patients’ interest – everyone is unique.

- Engaging different ages of children.

- Encouraging social connection – be careful with social networking as it is not always positive for patients suffering from some illnesses.

Current hospital play and ideas for future hospital play. Susan Davies from Birmingham Children’s Hospital.

Following Kevin Hartshorn, a group of play specialists talked about their current practice at the Birmingham Children’s Hospital and emphasised the changes made in the last twelve months of their practice. Their team of qualified play specialists are split into different categories: medical, surgical and youth services. They deal with both outpatients that are referred to them for treatment preparation and inpatients that they see frequently. The play environment at Birmingham Children’s Hospital includes a play centre and playground which allow the children to keep playing outside when the centre closes. The centre features multi-sensory areas and a kitchen, amongst other exciting things, and the play specialists usually works with young people in the hospital to design these spaces. They also propose a lot of creative activities and spaces for people to come down to from their ward. In terms of technology they have TVs and an iPad to take around the wards. They also recently got a 3D TV and some special games controllers for patients with limited movement.

Some challenging and important points were raised:

- Some children cannot always mix because of illness.

- Important for teenager to socialise in and outside the hospital.

- Important to encourage the children to get dirty and messy: “if they were at home they would stick their feet in mud and eat worms, but what we tend to find with the younger children is after being in hospital a long time they don’t like getting messy anymore”.

- Needle play: assess their understanding before but this gives them choice, control and understanding of the procedure, making them more familiar with it all. For example, by using safe needles to paint with or squirt water.

- Role play is also used as a technique to teach children how to behave when they receive the treatment.

- How to break the routine in the hospital (boredom).

- Give the child responsibilities e.g. reporting on what happened with their treatment/procedure to their parents.

After lunch, Medikidz Digital Director Adrien Raudashi introduced the children’s medical education company Medikidz. It’s aims are to teach children about medical conditions, by giving them access to information in a format they understand, thus they are more likely to retain information. Adrien highlighted in the past the lack of patient information specifically designed to deliver medical information to children. The decision to use comic books and superheroes to inform children about health issues was informed by research in which young people stated that these were two of the things that they wanted to see the most. In the comics, each super hero represents a different part of the body and takes the child on a metaphorical journey. Visually appealing, the comic books are accessible, easy to read and the narrative guides the reader through aspects of each illness. All their stories are based on real people’s stories.

Some challenges and relevant points:

- Creating content: how to take these very complicated facts and transfer them into a meaningful narrative for the reader?

- Comic format: breaks down barriers between peers.

- Digital potential (user experience). Considering the medium: phone vs laptop screen not the same experience for the users.

- What makes game appealing? Take them down to their fundamental parts and think how to re-apply those ideas to other formats?

- Short term vs long term engagement. Narrative is powerful, it can hold a person’s engagement much longer.

- Different types of feedback, short vs long term feedback, contributes to people’s engagement.

- Taking social network into consideration, where children have their own voice.

- Partnership with Oculus for affordable virtual reality to simulate immersive environment.

Later in the afternoon, Sarah McNicol also recognised the power of comics in her talk “Journeys, Battles and Engines: The potential impact on graphic medicine of patient emotions”. Before looking at the different examples that dealt with comics and health, she introduced her background in bibliotherapy, where books are used as a form of therapy, a method widely recognised since the 50s. Sarah’s presentation featured examples that questioned ways of dealing with the emotional impact of illness and discussed how comics were used as a medium to create a more intuitive and direct engagement with the patients. Comics allow the patients to have different interpretations of a story which encourages creativity and imagination. Sarah also highlighted the use of metaphor in comics as being useful, a way of taking something difficult and scientific and making it understandable and more memorable to a wider audience.

Finally, Jo Birch presented her research on the use of space in Sheffield Children’s Hospital. She introduced some findings from “Space to Care” (2007), a project which looked at children’s everyday experiences in hospital. Her research promotes a co-design approach and is concerned with how to make hospitals more child-centred, child friendly environments. For this project, she used interviews supported by field notes and child drawings with 255 in and out-patients across three sites. She mentioned the hospital as a challenging setting for research with children. Her study looked at what children would ideally like from hospital spaces. Using pictures, children and teenagers were asked to reflect on different spaces in and out of hospital, looking at the look of the room, the different elements and what kind of things would be scary for them. They found that decoration and emblems such as clowns or long plain corridors would be an increasing factor of pain. However emblems that were familiar or cultural icons would decrease this feeling of fear. They also looked at the hospital layout, the notion of order and tidiness, hospital sitting etc. The study emphasised that children have an important role in shaping their own experience of spaces. The kind of environment they like would feature familiar elements, not only from home but from any other familiar spaces such as school or shops. The study shows that people would always try to keep them occupied and to maintain daily routine. Jo emphasised that sometimes children would just sleep and watch TV, those things they would be doing when ill at home.

Workshop let by Andrew Godfrey.

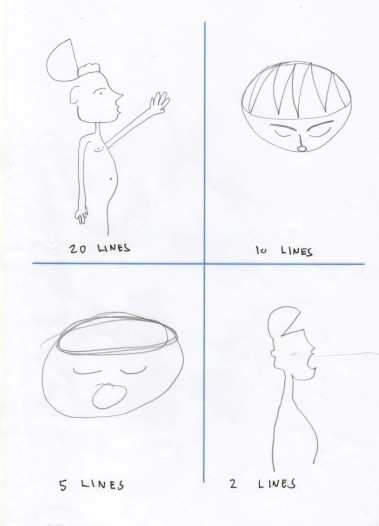

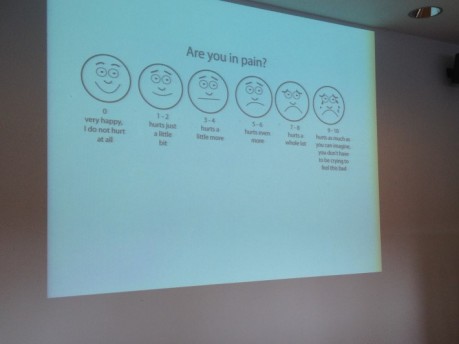

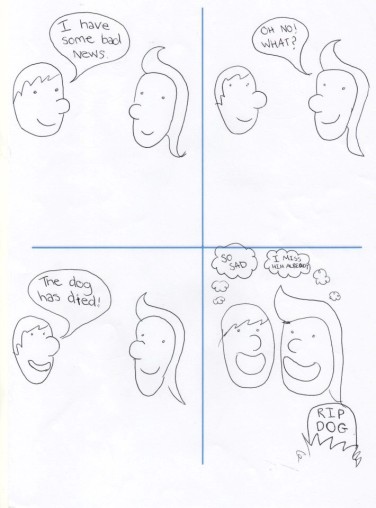

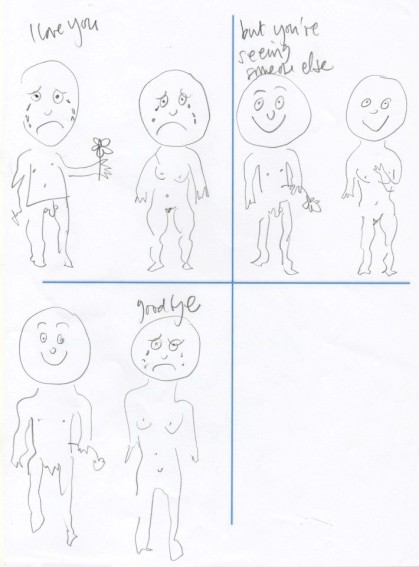

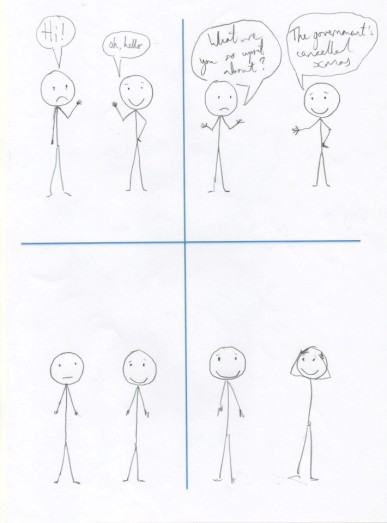

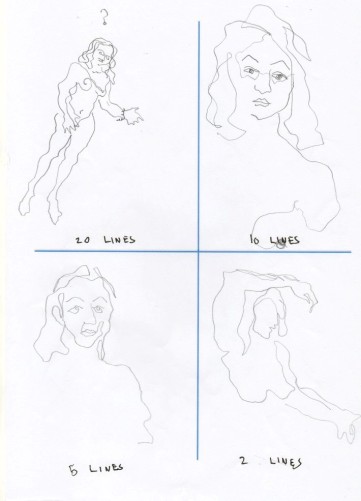

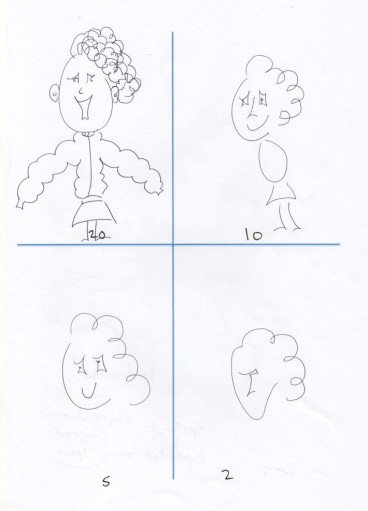

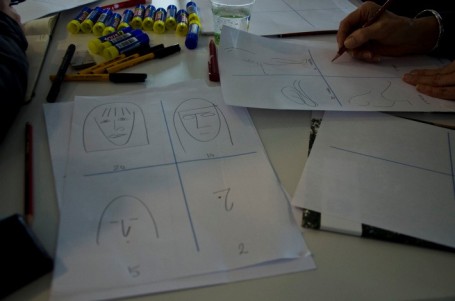

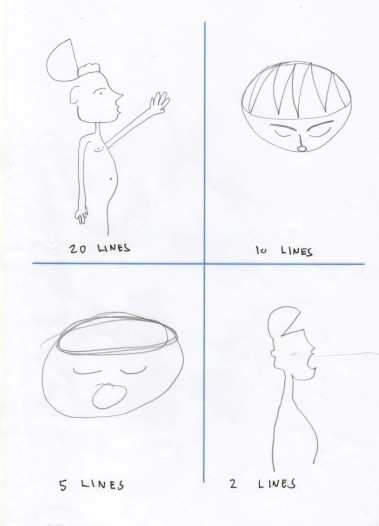

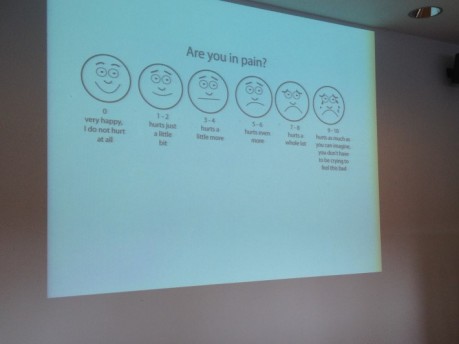

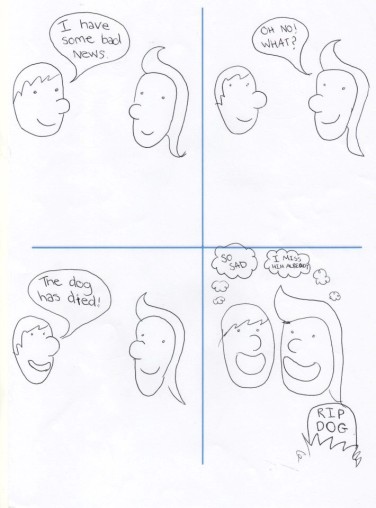

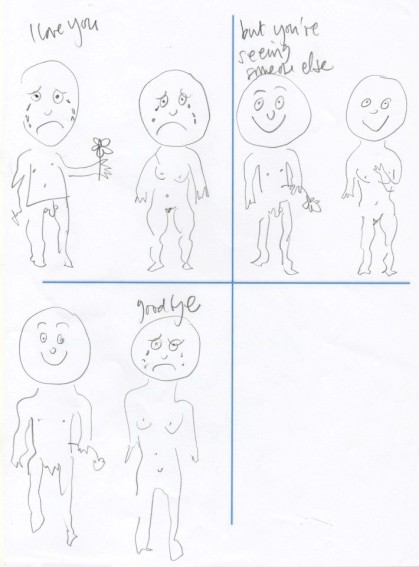

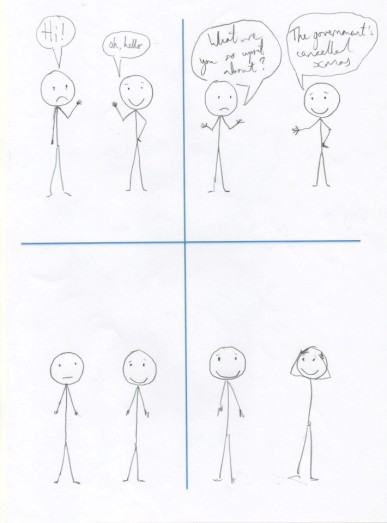

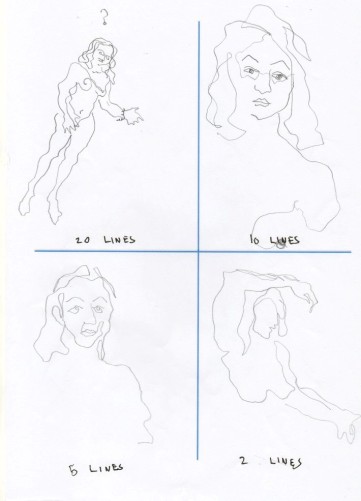

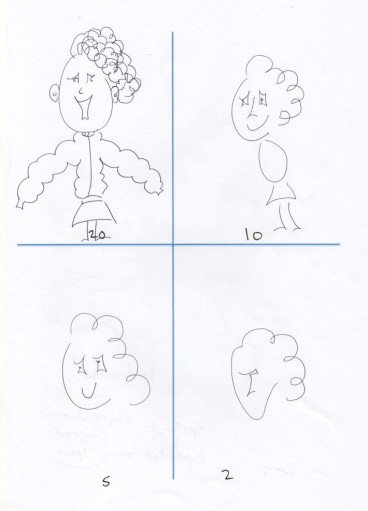

During the day, two artists gave short talks about their practice and led drawing workshops. First Isobel Williams talked about her Kancer Sutra project and showed examples of her work which she drew from “an uncomfortable position”, such as her work drawing in the Supreme Court where cameras are not allowed. Through her activities she challenged us to think about our childhood, what kind of “comforter” we used and still use, but also about darker themes. Later, Andrew Godfrey got us to draw a series of self portraits in 20, 10, 5 and 2 lines. Then, for the second exercise, he gave us a scale of pain (from happy to sad faces) and asked us to create a short comic, a conversation between two characters. The main constraint was to use the opposite emotion of what the characters were supposed to feel.

Participant’s self-portrait drawing. Workshop led by Andrew Godfrey.

Slide from Andrew Godfrey

Participant’s drawing featuring a short comic where faces of what characters were supposed to feel are swapped. Workshop led by Andrew Godfrey.

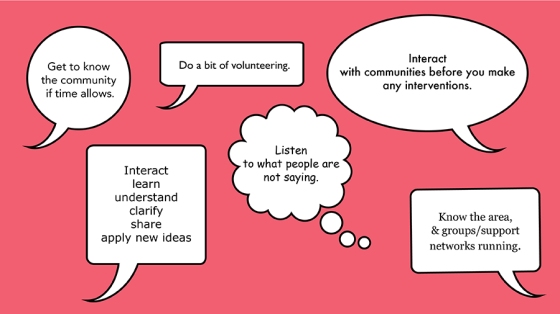

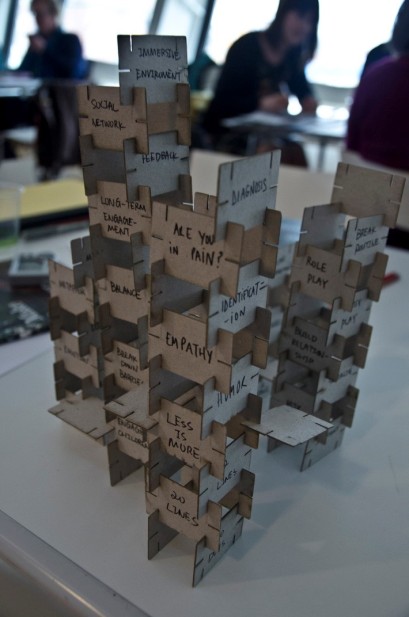

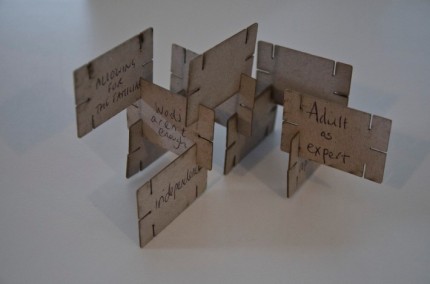

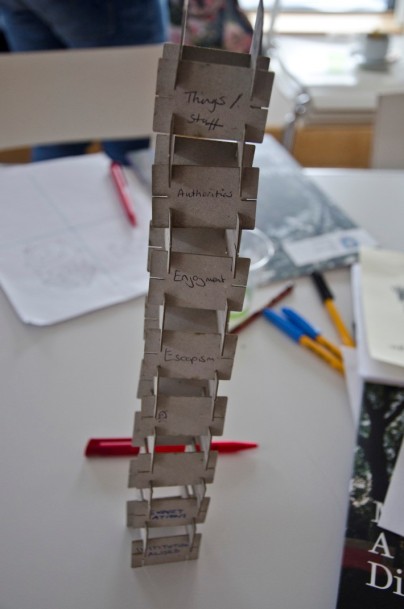

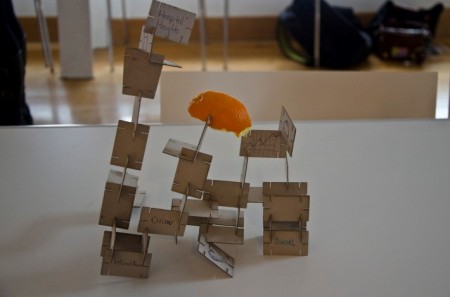

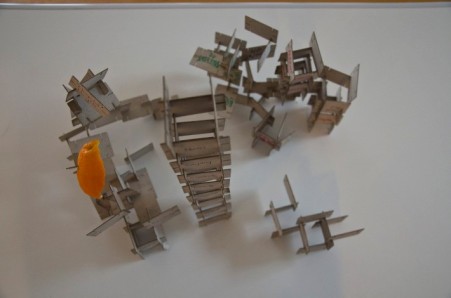

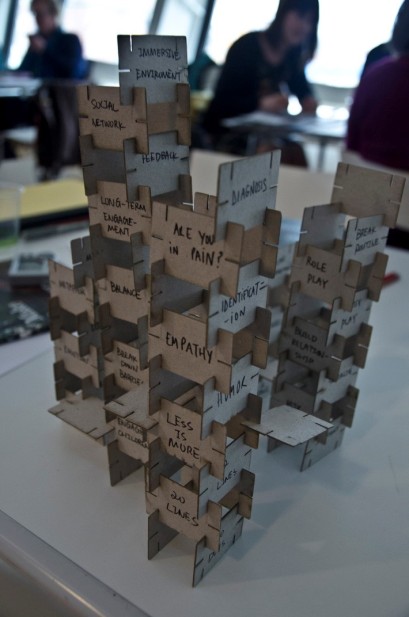

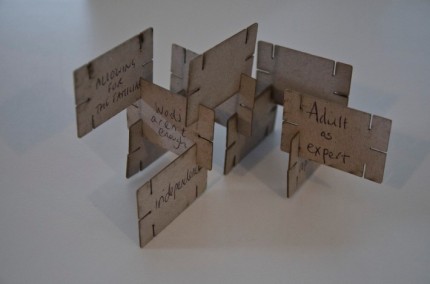

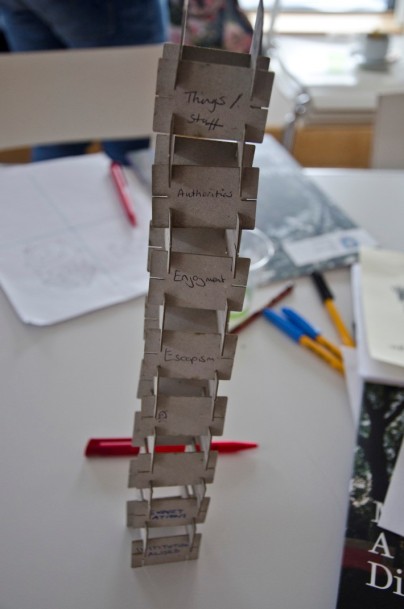

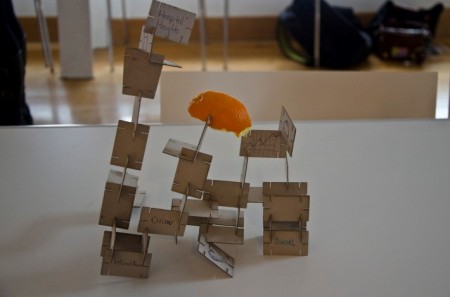

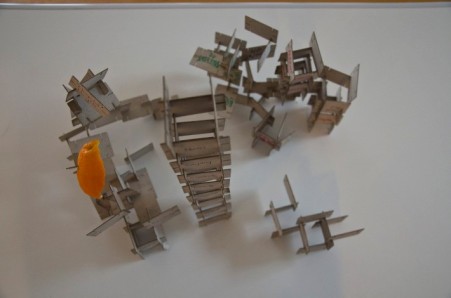

For our wrap-up at the end of the day we projected a constellation of keywords from all the talks and workshops on the walls and we gave each table a set of cards we recycled from our little movie Dreamland, which explores themes of imagined space and isolation. We asked everyone to have a conversation and write down words to finally build a little model together out of the cards. We gave them ten minutes and then, we asked each group to talk about their model in order to conclude the day. The list of keywords we projected was meant to help them start a conversation on key points from the day. We also displayed our own model from the day, each tower represents a talk or workshop and features keywords from it.

The first group emphasised the importance of recognising children’s imagined spaces and physical ones but also the meanings children attach to their experiences.

Emotional journeys/independence/objects/home/flexibility/narrative is placed/words are not enough/adult as expert/imagined space.

One participant from group 2 explained “were very uncollaborative, we wrote our own words and built them together at the end”. They talked about entertainment vs quietness. According to them, it is not always about feeling things and talking about it. This group emphasised the importance of paying attention to children and being attentive to what is going on without necessarily engaging in a conversation which some children will find difficult.

Culture/sugar coating illness/rights/institutionalised/escapism/quiet/listening/connection/everyday/authorities/voice/hear me/stories/things/stuff/space/safe-guarding/social/space/assumptions/smile/expectations/creativity/enjoyment/beliefs/stones/feelings

Group 3 stuck everything together a bit randomly. One participant explained that the fact of doing it – the simple pleasure of putting things together – was interesting and stimulated conversation. Also we noticed that words would get randomly next to each other which encouraged imagination and new ideas to emerge.

Narrative situation/emotions/engagement/needle/practice/med info/no Words/empathy/identification/social/isolation/sound/the function of play/into practice/narrative/agency/play/parallel lines/familiar/parent Ill/active/solipsistic/dissonance/peer/euphemism/play/earnest/augment/small/alienated/environment/metaphors/clowns/needles/graphic/simplicity/play/inpatient/emotion/grotesque/fear/only images/gamification/passive/children/child’s perspective/playing with fear/actual fear/needles and pins/whose narratives?/size/scale/prospective/ways of knowing/adult/children/gifts/panels/selective/mute.

Finally the last group embraced the concept of free play. One participant added: ‘we have played, that’s what we’ve done!’

Young people/blood/communication/honest/control/social/exciting/interactive/hospital heights/draw

Below more participants’ drawing.

For more information on this project and further posts on the thinking processed involved in this project please visit http://iedgameresearch.wordpress.com/